Situated in what now constitutes the border triangle between Switzerland, Germany and France, historically the Basel region has almost always been at a frontier. Even at the turn of the last-but-one millennium, Basel was the meeting point of the Holy Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Germany and the Duchy of Burgundy. Its more modern history begins with the shockwave that emanated from the French Revolution in 1789. The first refugees arrived in the area just one week after the storming of the Bastille. When Revolutionary France then declared war on Austria in 1792, Basel suddenly found itself in the middle of a European civil war. In 1797, a vast French army marched on the Old Swiss Confederacy from the west. Basel surrendered immediately. On 20 January, the Grand Council accepted the Revolutionaries’ demands and abolished serfdom. Basel had been revolutionised in no time, without a drop of blood being shed.

French troops were not unfamiliar in the region, having occupied the Prince-Bishopric of Basel in 1780 and annexed it to France in 1793. In fact, the city had not had a bishop since the last one was removed in 1529 in the course of the Reformation. His diocese ended in the South in what were then the villages of Reinach and Arlesheim on the river Birs, a tributary of the Rhine. With it now integrated into France, the village just north of Münchenstein suddenly became a border post. What are now the Basel-Landschaft municipalities of Arlesheim, Aesch and Reinach were in French territory, while by the grace of Napoleon Basel and Münchenstein belonged to the Helvetic Republic.

City society at the time was dominated by rich merchant families that had been producing silk ribbons for the whole of Europe from their factories in the upper Basel region since the 17th and 18th centuries. They needed something in which to invest their accumulated wealth, and so turned to commercial products of all types and new and promising industries such as schappe (spun) silk and the new electrical technology, as we will see later. The urban middle class of crafts and tradespeople, organised into guilds, lived in constant fear of competition from rural artisans.

After the French were defeated at the Battle of the Nations at Leipzig in 1813, Napoleon retreated back behind the Rhine. The coalition troops that had defeated Napoleon and were pursuing him to France initially advanced as far as the knee of the Rhine. Basel once again had to capitulate to a superior power. On the morning of 21 December 1813, 80,000 soldiers crossed the Medieval bridge in central Basel and occupied the former Prince-Bishopric.

Basel was then allotted to the Swiss Confederacy by the Congress of Vienna in 1815. The area extending from Allschwil to Arlesheim and Aesch, which was still Roman Catholic, went to the canton of Basel, while the southern regions below the Angenstein gorge became part of the canton of Bern. At a stroke, formerly Protestant Basel was now home to 8,000 Catholics. The Basel Council was uninterested in genuine equality between the two denominations, however. Freedom of expression was also restricted at first, before being prohibited entirely.

Resistance in the countryside began to mount, fired up by these heavy-handed changes to the law, in addition to unnecessary provocation by the city’s troops. Tensions continued to rise, culminating on 3 August 1833 in the famous decisive Battle of Hülftenschanz. The city forces suffered a humiliating defeat. The Tagsatzung, the meeting of delegates from the individual Swiss cantons and the highest arbitral power in the Old Confederacy, ultimately ruled that the canton should be divided completely into the cantons of Basel-Landschaft (the countryside around Basel) and Basel-Stadt (the city itself). It ordered that the original canton’s assets be shared accordingly. The small territory of Basel-Stadt had lost all free to its Swiss allies.

Amid the upheaval, Basel’s wealthy families continued to invest in promising sectors of industry. As part of this they acquired land in Münchenstein, Arlesheim and other municipalities, becoming the drivers of industrialisation in the young canton of Basel-Landschaft.

In 1824, businessman Johann Siegmund Alioth (1788 – 1850) purchased the first schappe factory on Hammerstrasse in Basel to produce spun silk (a product inferior to true single-filament silk). Born in Biel, as a 16-year-old youth he was apprenticed in 1804 as a clerk to the firm of Forcart-Weiss & Söhne. Here, he spent six years in training, becoming familiar with the personal and business environment of a rich silk ribbon family. In 1829 he took over the site north of the Bruggmühle in Arlesheim, from where he built up the largest and most important schappe silk spinning mill in Europe. Schappe processing was not directly linked to the local silk ribbon industry, because its raw material originates from the waste from Italian silk production. The Alioth company found reliable workers among young farmers’ daughters. The men in the municipalities on the outskirts of Basel were almost all employed in agriculture. Only the women and daughters had any free capacity. This proved decisive to the industrialisation of the canton of Basel-Landschaft.

When Johann Siegmund Alioth died in 1850, the businesses were taken over by his eldest son Daniel August Alioth and his brother Achilles. Daniel’s two sons Willhelm (1845 – 1916) and Ludwig Rudolf (1848 – 1916) later also joined the family firm. Just before the turn of the 20th century the European silk-spinning industry was facing a wave of consolidation. Daniel August Alioth and his son Ludwig Rudolf left the company in 1881, when the Bankverein (now major Swiss bank UBS) founded the Societé Industrielle pour la Schappe (SIS).

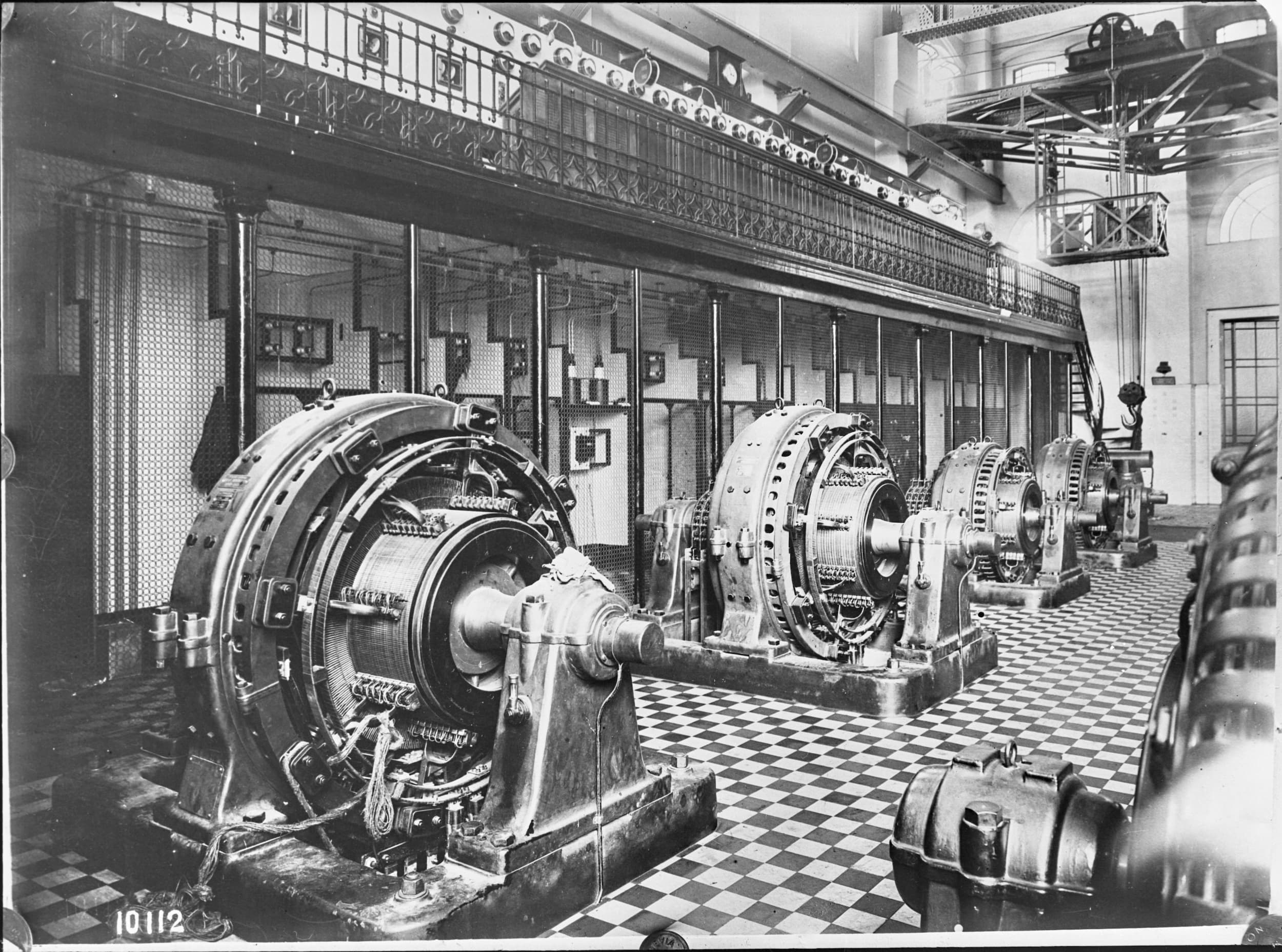

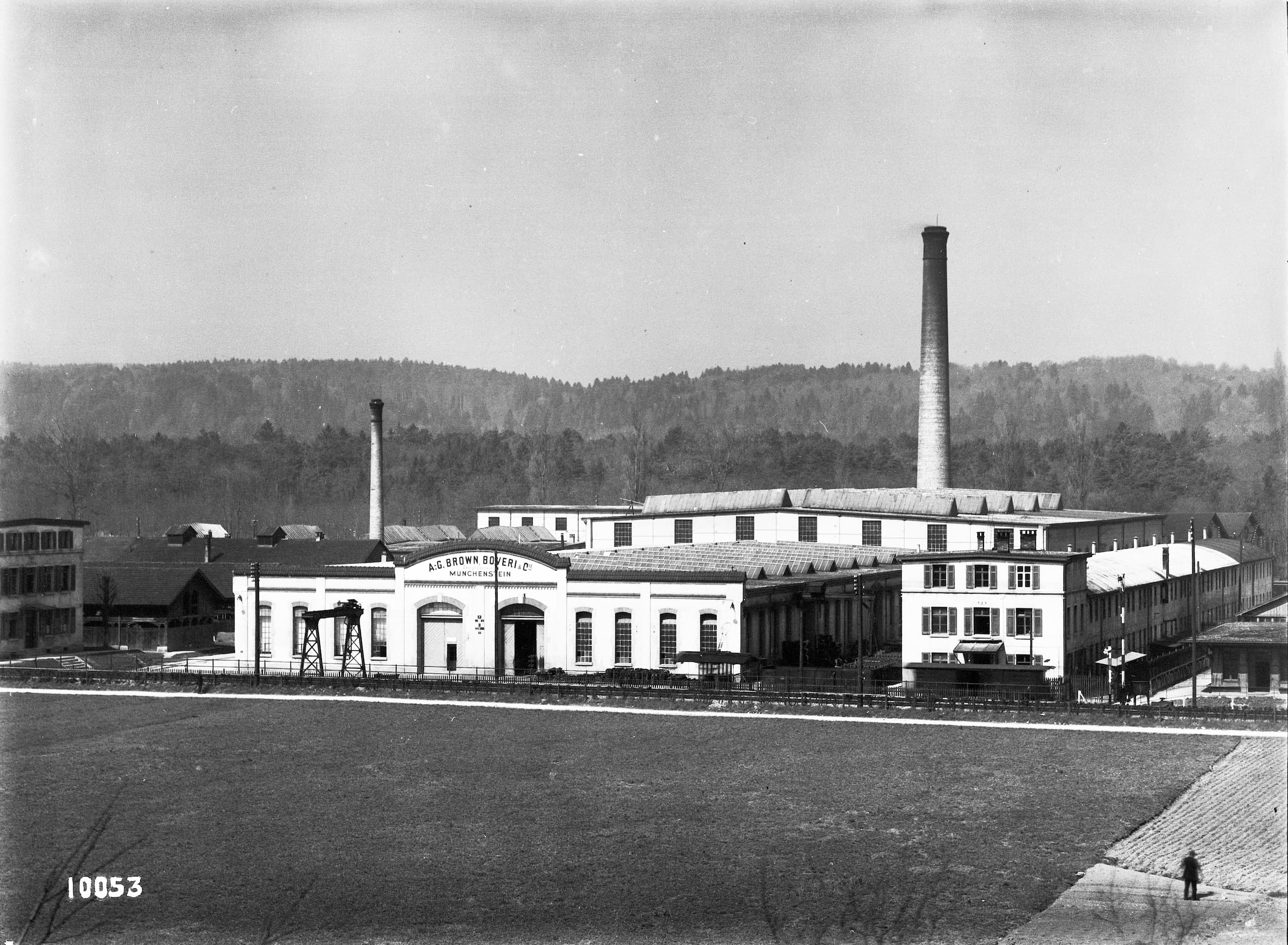

That same year Ludwig Rudolf Alioth went into business with inventor Emil Bürgin, opening a small factory for electrical machines in Basel under the name of R. Alioth & Cie. After differences of opinion with the city of Basel in 1885 about the development of an electricity grid, Alioth immediately moved his head office to Münchenstein. Having probably learned from his grandfather that business success was tied to size and market relevance, in 1886 Alioth purchased a large plot of land of over 40,000 m2 in neighbouring Arlesheim. He began right away to build a production plant with factory floors larger than anything seen before in the region. By no later than 1900 the Elektrizitätsgesellschaft Alioth AG (EGA) was making a name for itself around the world, delivering dynamos of up to 600 HP to Spain, France and Italy.

The central railway line from Basel to Olten opened in 1858, connecting Basel to the network in Switzerland’s central plateau. Initially, the Basel government then regarded a second line through the Birs valley as unnecessary. Then war between Germany and France broke out again in 1870, and the water route via the Rhine was blocked once more. Under the Treaty of Frankfurt in 1871, Alsace was ceded to the German Reich, cutting off overnight the direct export route to France, and thus also the connection to the French railway system. The new route had to go through the former Prince-Bishopric of Basel, along the Birs and via Porrentruy, to get straight into France.

President Dr. Thomas Staehelin at the launch of uptownBasel.

Münchenstein immediately began to campaign for the railway line to be laid via Münchenstein and Arlesheim and not on the other side of the Birs, along the river via Reinach and Aesch to Angenstein, which would actually have been easier. In the end the cantonal government did actually decide that the line would cross the Birs at Münchenstein. Industry was already established on this side, with the schappe mill at Arlesheim. As a result, the population had also grown, so there was plenty of labour available.

Time was of the essence. It was imperative that a direct connection to France be put in place without delay. It seems that building work was rather hasty, however, as on 14 June 1891 the eastern bridge support failed under the weight of several tonnes of train. The bridge collapsed, killing 73 mainly young people. Switzerland had experienced its first major railway incident. The railway nonetheless performed three important functions: it transported raw materials and finished products, it was an employer, and it offered a means of transport for the commuters who were now able to travel longer distances to work in the factories.

Ludwig Rudolf Alioth soon realised that he needed more than just nimble female fingers to assemble his electrical motors. He would have to develop, test and manufacture new products. However, he was unable to find the engineers he required because the University of Basel lacked the money to offer new study programmes such as electrical, mechanical and hydraulic engineering. Only the federal government-funded Polytechnikum in Zurich (now the ETH) was able to offer these subjects. In 1911 Alioth sold his company to Baden-based Brown Boveri & Cie., but locomotives continued to be built in Arlesheim until after the Second World War. In 1988, BBC merged with the Swedish firm Asea to create what is now ABB. It marked the definitive end of the Münchenstein works.

Despite a multitude of plans, this huge site remained almost unused for some 20 years. Finally, in 2012, uptownBasel began negotiating with the then owner, the canton of Basel-Landschaft, to buy the land. Now we have come full circle. The place where the industrialisation of the Basel region began now provides the launch pad for Industry 4.0.